Tim Upperton’s poetry and fiction have appeared or are forthcoming in AGNI, Bravado, Dreamcatcher, Landfall, New Zealand Books, New Zealand Listener, North & South, Reconfigurations, Sport, Takahe, Turbine and Best New Zealand Poems 2008.

Tim has won first prizes in the New Zealand Listener National Poetry Day Competition, Takahe magazine’s poetry competition, and the Northland and Manawatu short story competitions. He is a former poetry editor for Bravado, and tutors creative writing, travel writing and New Zealand literature at Massey University.

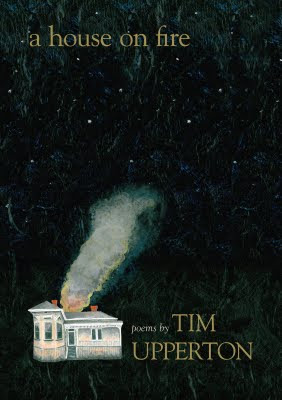

Tim, your first collection, A House on Fire, was launched on Montana Poetry Day, Friday 24 July, in Palmerston North. What are the key things that you would like prospective readers to know about this collection?

It’s a various collection, ranging across different forms and engaging with familiar aspects of domestic life as well as with things that interest me but which are remote from my daily concerns. So one poem is about making lunches each day for my four children, and another is about history as successive erasure, one forgetting piled on top of another. The first poem I ever published is in the collection, and that was ten years ago. And the most recently published poem, “History”, is also there, and appeared in New Zealand Books in June. So the collection is a record, I guess, of my published writing over a decade.

Is the collection representative of your poetry as a whole, or does it focus on one or more particular aspects of your poetry?

It’s representative in that most of my poems have found their way into it! Though there are exceptions: a few poems that have been previously published in magazines didn’t seem to belong, and have been omitted.

How did you become involved in writing poetry? Which, if any, poets have been most influential on your writing?

I studied literature – mostly English – at university, and had some ambition to be a writer, without actually writing very much. I wanted to write fiction, but the first piece of writing I submitted was a poem, and I was lucky to have it published in Sport. So of course I submitted a further batch of poems to Sport, which were duly rejected. And that was the start, for me – I kept writing, kept submitting, and the rejections and the acceptances came in. Fail better, as Beckett says. It took me a long time to realise that you don’t have to be very smart to write poems. I don’t think I have any particular wisdom to offer, and I’m bored generally by poets who do. Language is smart, so I don’t have to be – I try to listen to language, alert to the wisdom that’s inherent in it. And I arrange it on paper, a bit like shaking a kaleidoscope and looking to see what patterns emerge.

I often look to overseas models – British and American – when writing my own poems, and often not-so-recent poets with a formalist bent – Elizabeth Bishop, Weldon Kees, Sylvia Plath, Ted Hughes, Theodore Roethke. But lately in my capacity as poetry reviewer for Bravado I’ve been reading and enjoying a lot more contemporary New Zealand poetry. And I’ve been teaching New Zealand literature at Massey University this year, so I’ve been reacquainting myself with Curnow, Bethell, Baxter and so on. I admire the sense of place in contemporary New Zealand writing – there’s an ease and confidence there that I would wish to emulate.

I very much enjoyed my introduction to the Palmerston North poetry scene in June, when I visited to read as part of the Stand Up Poetry series. Do you regard yourself as an active member of that scene, or do you prefer to work away on your own for the most part?

Well, I’m active in that I attend most poetry gatherings, and there is a lot going on – tonight, for example, I’m reading with half a dozen other poets at Te Manawa, the Palmerston North museum, and that will be the third poetry event I’ve attended this week. Such events are fun, and they draw surprisingly large audiences, but they’re in stark contrast with the actual business of writing, which is generally solitary and difficult.

On July 20th, you and many of the other poets whose work is included in Best New Zealand Poems 2008 read together in Wellington. What did it mean to you to have a poem chosen for this collection, and did you enjoy the reading?

I was very pleased to have a poem included in Best New Zealand Poems. It is of course one person’s – in this case, James Brown’s – take on what is best; the selection process is hopelessly subjective. But I found myself in good company, and I caught up with a few friends on the day, including you! It’s a pleasure – and this is true also of the local events I mentioned previously – to be among people who take poetry’s importance and centrality as a given.

You teach creative writing at Massey University. Does working as a creative writing teacher have a good (or even a bad) influence on your own practice as a poet?

It must be a good influence, as I’m writing more these days than I did when I worked as a manager in local government. Writing is a series of delicate decisions, and as I review the decisions my students have made, I can’t help but reflect on my own.

You have been a poetry editor, and judged poetry competitions. I’ve enjoyed the editing I’ve done, but found that I don’t write much poetry while I’m looking at lots of other people’s poetry submissions. Has this been a problem for you?

Yes, my experience has been similar. I enjoyed editing, and also judging the Bravado poetry competition last year. But the work seemed to use up the writing part of my brain, and I didn’t produce many poems of my own at that time.

Turning away from poetry for a moment, I was intrigued by some comments you made, when we talked in Palmerston North, about your dislike of narrative in short fiction. Would you care to elaborate?

It’s of course a very general comment, and I can immediately think of exceptions. I’ve just reviewed Charlotte Grimshaw’s volume of linked short stories, Singularity, for example, and I admired it very much. But as a general comment, it’s true – narrative doesn’t particularly interest me. All that cause-and-effect, establishing motive, character development, the workings of plot – it’s like some rusted, obsolete machine cranking away. I love the economy of poetry – a short lyric poem can convey an effect that it may take a whole novel to produce. I can see that this is a personal prejudice. The contemporary fiction that interests me most is the kind that upsets our expectations of narrative – W.G. Sebald’s work, for example.

Finally, what literary project or projects are you now working on?

I’ve started writing poems again, which is a relief after some months of grooming my already-written poems for book publication. I sincerely hope my next collection won’t take as long to write as my first one.

Kindness

by Tim Upperton

Evening light, olive oil

poured from a high jug: streaming

over the burnished back of the cricket

riding its bowing grass stem; glossing

the spade with its broken handle

leaning on the strainer-post that is itself

leaning, its crumbly lichen glowing,

the wire tired and slack; pooling

on the surface of the leylandii stump,

with its surround of buttery chips

from inexpert swipes of the axe.

Light is light, it is not kindness,

but if kindness had a colour, perhaps

it would be this – yes, you turn away

impatiently, yet it’s you who cannot

bear to crush a snail; who once, in heavy

traffic, abandoned the car, and in tears

strode to a maimed pukeko that fluttered

beside the wide road; you who killed

that bird with a swing and a crack –

stay with me, as the light goes

from gold, to grey, to black.

Book availability

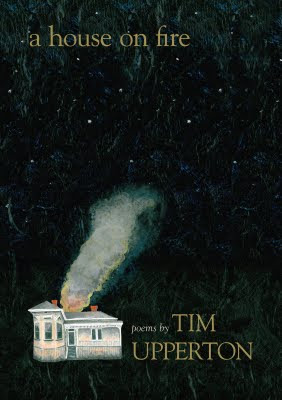

A House on Fire, by Tim Upperton, Steele Roberts, 61pp, $19.99, ISBN 987-1-877448-68-3

Available from:

- The publisher (www.steeleroberts.co.nz)

- Bruce McKenzie’s, Palmerston North

- The author (t.l.upperton (at) massey.ac.nz)

- Or by ordering through your local bookshop