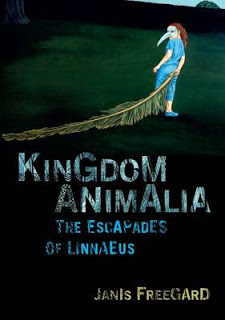

Janis Freegard is a Wellington-based writer of poetry and fiction. She was born in South Shields in the North-East of England and spent part of her childhood in South Africa and Australia, before her family settled in New Zealand. Her poetry collection, Kingdom Animalia: The Escapades of Linnaeus, was published by Auckland University Press in May. Her writing has appeared in many journals and anthologies including AUP New Poets 3, Big Weather: Poems of Wellington, Voyagers: Science Fiction Poetry from New Zealand, The Iron Book of New Humorous Verse, The NZ Listener, Landfall, The North (UK), JAAM, Poetry NZ and Trout. She works in the state sector and lives in Vogeltown with an historian and a cat. She also has a blog: http://janisfreegard.wordpress.com

Janis’ poem A Life Blighted By Pythons was my Tuesday Poem this week.

First things first: why Linnaeus?

I wanted the book to have some kind of structure. As the poems were about animals (or at least had an animal in them somewhere), it seemed like a good idea to arrange them according to their taxonomic classification. I’d learned a little about taxonomy at university and when I worked at the Department of Conservation (trying to prevent trade in endangered species).

Our modern classification system has so many categories, though, that I soon realised it was going to be too hard to write poems for every different class of animal. That’s when I hit on using Linnaeus’ six groupings (mammals, birds, amphibians, fish, insects and worms). Linnaeus was the eighteenth century Swedish naturalist who came up with the two-word classification system for plants and animals that we still use today (such as Homo sapiens for human beings).

Once I started organising the poems into the six categories, I decided to write about Linnaeus himself as well. He was an extraordinary man. I can’t help but admire his commitment and tenacity in trying to categorise every plant, animal and mineral on the planet.

More generally, why zoology? (As someone who can proudly boast of being a BSc in Botany (Failed), I am naturally hoping that the other kingdoms will get a look-in in future collections. I can’t help feeling that the Archaea, for example, are not well represented in contemporary poetry.)

I agree that the Archaea are sadly neglected, and I hope poets everywhere will rise to the challenge of remedying that! I have a Botany degree, so zoology might not seem like an obvious choice. But I do seem to write a lot of poems about animals and I thought the animal kingdom would be a good theme for a collection.

I very much enjoyed your selection of poems in AUP New Poets 3. Is there a lot of continuity between those poems and the poems in Kingdom Animalia, or do the new poems mark a sharp break with your previous work?

Thanks Tim. Several of my poems in AUP New Poets 3 have animals in them (such as the ‘Animal Tales’ sequence) so I do think Kingdom Animalia carries forward some of the strands from that selection. Both books also contain some prose poems and both have elements of surrealism.

If someone described you as a “nature poet”, would you be pleased, alarmed, indignant, or unruffled?

I don’t mind being described as a nature poet, but I’m not sure it gives the full picture. Perhaps I could be a sometimes absurdist nature poet who also writes about life in the city and love.

You are great at running fun, memorable book launches. How do you manage it?

Thanks Tim, and thanks for coming to the launch! I see a book launch as an excuse for a bit of a party – I want people to feel entertained and enjoy themselves. And the planning is just as much fun as the event. I had such a good time designing the invitation, choosing the venue, making the fresh asparagus rolls and dressing up in a bird mask (like the one on the cover of the book). I also had some great helpers on the night.

My knowledge of your work is mainly through your poetry, but it is bookended by fiction; I first heard your name when your story “Mill” won the Katherine Mansfield Award in 2001, and I’ve just received my copy of the Christchurch earthquake appeal fundraising anthology Tales for Canterbury, which includes your story “The Magician”. Have you kept writing fiction as well as poetry?

Yes, I’ve always enjoyed writing both poetry and fiction, although at times one takes precedence over the other. Poetry had the upper hand while I was focusing on Kingdom Animalia and now I’m getting back into fiction a bit more. I haven’t written many short stories over the past few years, though, as I’ve been focusing on writing a novel. Sometimes the lines between poetry and fiction get a bit blurry – I like writing prose poems, which seem to belong in the grey area between the two.

Is being a member of a writing community important to you, or could you work away just as happily in isolation from other writers?

I really value opportunities to interact with other writers. I belong to a long-standing poetry group that meets monthly to share poems and give each other feedback. I often take along poems that aren’t quite working and it’s very useful to hear others’ thoughts on how I might improve them. It also means I get to read everyone else’s excellent poems. I also enjoy being part of the New Zealand Poetry Society and going along to Poetry at the Ballroom Café in Newtown.

I belong to a great fiction writing group too, which has been meeting for about eight or nine years. I could work away quite happily on my own, but it is good having the groups. They also act as a helpful spur to write.

Which poets would you recommend to readers who enjoy your poetry?

People who like my poetry might also like Vivienne Plumb’s work (I know I do) and Mary Cresswell’s (ditto). I have too many favourite poets to list them all (and my poetry mightn’t have much in common with theirs) but I’d have to include (alphabetically) Simon Armitage, Jenny Bornholdt, Selima Hill, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Roger McGough and Bill Manhire. I like punk era performance poets too, like Patti Smith, John Cooper Clarke and Linton Kwesi Johnson. And I’ll go and watch Sam Hunt read any time I can.

Similarly, who are some of your favourite fiction writers?

Jeanette Winterson’s top of the list – there’s one of her short stories (The 24-Hour Dog from The World and Other Places) that I have read over and over and every time I read it, I think: I might as well give up writing now because I’ll never be able to write something that good! Sometimes I just read the first paragraph and sigh because it’s so wonderful. I’m also a big fan of Canadian writer Jane Rule (one my favourite books is This is Not for You), Jean Watson (Stand in the Rain, The World is an Orange and the Sun, The Balloon Watchers, Three Sea Stories), Noel Virtue, Lewis Carroll, Banana Yoshimoto (I’ve just finished reading The Lake), Ronald Hugh Morrieson, Haruki Murakami, Sarah Waters and Tove Jansson (better known for the Moomin books, but her adult fiction is also wonderful, in a very understated, quiet way). I could rave on, but I’ll stop there.

Finally, if you don’t mind me asking, what projects are you working on now?

I’m working on two poetry collections (which may converge eventually) and I’m finishing the first draft of a novel. I’m also planning a collaboration with an artist.

How To Buy Kingdom Animalia

Kingdom Animalia is available from most book shops that have a good poetry selection, such as Unity Books, university bookshops and Te Papa, and many online booksellers, including Fishpond and Wheelers, or people can get it directly from Auckland University Press.