In 1976 Chris Bell was the youngest poet to have been published in Norman Hidden’s British small press magazine ‘Workshop New Poetry’, which later championed British Poet Laureate Andrew Motion, among others. His short stories have appeared in ‘The Third Alternative’ (UK); ‘Grotesque’ (Ireland); ‘The Heidelberg Review’ (Germany); ‘Transversions’ (Canada); ‘Not One of Us’; ‘Zahir’ (US) and ‘Takahe’ (New Zealand), as well as on the internet. ‘The Cruel Countess’ was anthologised in The Year’s Best Fantasy & Horror (10th Annual Edition), published by St Martin’s Griffin Books, in which his collection The Bumper Book of Lies received a couple of Honourable Mentions.

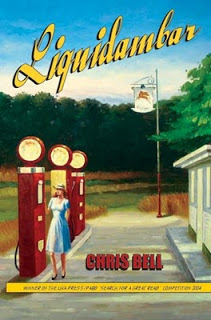

His short-short story ‘www.sadbastard.co.nz’ appeared in the 2005 Random House New Zealand anthology Home. Liquidambar, his first novel, was the winner of the 2004 UKAuthors and PADB’s ‘In Search of A Great Read’ novel-writing competition. His story ‘Shem-el-Nessim’ was anthologised in the PS Publishing anthology This Is The Summer of Love and received an honourable mention in Ellen Datlow’s anthology The Best Horror of The Year (Datlow’s choice of honourable mentions was described by Amanda Spedding of the Innsmouth Free Press as “an extraordinarily strong collection”) and it’s about to appear in the Constable & Robinson-published anthology The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror. It isn’t a horror story.

After finishing Liquidambar, Bell wrote the first draft of a novella, ‘Saccade’, completion of which has been interrupted since the birth of his son Frank (named after Zappa), now two and a half years old.

To start at the end, you say on your website that your most recent short story, ‘Iniquity’, which you’ve made available on the site, is “perhaps the last short story I will ever write”. Why, and what comes next?

“I began submitting short stories to small press magazines in the 1980s. Before that, in the 1970s, I’d suffered the multiple blunt head trauma of rejection and disappointment from submissions to countless small press poetry magazines. While I acknowledge the value of rejection for writers (no irony intended), it’s become increasingly common and I don’t feel that’s a comment on any dwindling in the quality of my writing.

“Over the years, publishers have become increasingly slow to react and less likely to accept unsolicited work. Where once I was able to sell a story to multiple small press markets simultaneously, these days publishers increasingly demand exclusivity in return for not very much. As a full-time father, writing became a luxury I can rarely afford or find time for. I’ve decided it’s too difficult to fully explore my material. I may at some point finish my novella, and it would of course be tempting fate to claim ‘Iniquity’ is definitely my last short story, but I’ve succumbed to the law of diminishing returns.”

Your short story ‘Shem-el-Nessim’ has just been accepted for the forthcoming edition of The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror, edited by Stephen Jones. I see that ‘Shem-el-Nessim’ was first published in 2006. What was the path from first publication to anthology selection?

“I decided to serialise the publication of ‘Shem-el-Nessim’ on the group blog NZBC in order to speed its completion. Prior to that I’d been working on it for about a year. It’s an homage to 1920s ghost stories and so was a tricky one to get right. It had previously taken me a weekend at most to finish a raw, first draft of a story. I then began submitting ‘Shem’ to the usual suspects: small press magazines around the world. After the customary half-dozen rejections it was accepted by Pete Crowther at PostScripts and Sheryl Tempchin at ‘Zahir’ magazine in the US. I can only assume Stephen Jones saw it in the PostScripts anthology, This Is The Summer of Love, as his contract arrived out of the blue. A rare and pleasant surprise.

“It hasn’t been a universally well-liked story, though; for some inexplicable reason the British Science Fiction Association took exception to it. Although why they even bothered reading it let alone commenting on it when it isn’t science fiction I’m not sure.”

You’ve had another notable success in getting into a major anthology, too. How did that come about?

“The St Martin’s Griffin Year’s Best Fantasy & Horror in 1996 occurred after my story ‘The Cruel Countess’ appeared in ‘The Third Alternative’ (now Black Static magazine) and several other places. It was chosen by speculative fiction mavens Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling and its selection was helped by a favourable review of my collected stories, The Bumper Book of Lies by Paul di Filippo in ‘Asimov’s Science Fiction’ magazine. Paul has subsequently supported more of my writing and offered his advice.”

How did you get your start in writing, and in getting work published?

“My first ever published story, ‘On Formosa Street’ (which is also the first real story I completed, and the first in my mainly chronological collection The Bumper Book of Lies) was published by Isa Moynihan in the New Zealand magazine Takahe long before I considered migrating here.

“While I was still in primary school in Wales, one teacher would let me work alone in the school library. He’d give me a photograph that had been cut out of a magazine (I vividly remember one of a Viking with a burning village in the background) and let me write something about the picture while the rest of the class was working on maths or something boring. That was a formative influence. Another great teacher and mentor was my secondary school English teacher Ken Walsh, who read to us from Alan Sillitoe’s ‘The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner’ and various Ted Hughes and R.S. Thomas poems in class.

“I’ve always loved books, but it was almost certainly discovering Russell Hoban’s extraordinary books in the early 1980s that convinced me I wanted to be a writer.”

What is it that so impresses you about Hoban’s writing?

“He speaks to me on a frequency I’m tuned into. What he’s said about the ‘limited reality consensus’ we all live by, whether unconsciously or consciously, rings true — the sheer strangeness of existence we deny in order to pay the rent and get mundane things done. The fact that you and I are in different places having a ‘conversation’ about this right now is deeply and inarguably odd.

“It takes you all your life to learn what you’ve learned about great art. And one of the innumerable things Russ’s writing has taught me is that it’s impossible to imitate art. What I mean by that is that, even if you can figure out how to mimic someone’s phrasing and style, it’ll always be second-rate because it wasn’t your idea. You can’t deliver it with the totality and completeness of the creator.

“This applies to writers as much as it does to musicians. I’ve almost made a life’s study of Jaco Pastorius’ basslines. Even dissecting them and playing them back at the same pitch but half speed — which every learning musician can now do, thanks to digital technology — there’s an almost imperceptible ‘invisible’ quality between the notes, under the moment, something about the way he constructed and executed his lines that makes it impossible to impersonate every phrase exactly or write it down. Musicians who’ve studied Miles’ playing or Bird or Coltrane will know what I mean. To be brutal, it means only other musicians or writers can appreciate their peers at this level, and it distances artists from the average listener. As a writer, your ear is everything.

“I’ve always learned by absorption. Either that, or what skill I have was in my genetic code from the start.”

What adage do you aspire to live by?

“A couple spring to mind: ‘Be regular and orderly in your life so that you may be violent and original in your work’. Gustave Flaubert said that, and it applies equally to the work of both Frank Zappa and Russell Hoban. Just the other day, thanks to a member of the group of Hoban fans known as The Kraken, I stumbled on this from The Life and Work of Martha Graham:

‘There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all of time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and it will be lost. The world will not have it. It is not your business to determine how good it is nor how valuable nor how it compares with other expressions. It is your business to keep it yours clearly and directly, to keep the channel open. You do not even have to believe in yourself or your work. You have to keep yourself open and aware to the urges that motivate you. Keep the channel open … No artist is pleased. [There is] no satisfaction whatever at any time. There is only a queer divine dissatisfaction, a blessed unrest that keeps us marching and makes us more alive than the others.’

“I’d dearly love to have the courage to live by that adage.”

You’re a musician as well as a writer. Is it difficult to find the time and energy to do both, or do you find the two complementary?

“These days I treat playing music purely as a hobby and a therapeutic form of relaxation in an Oliver Sachs way, rather than a profession, which it was back in the 1980s. I find the two complementary in the sense that almost all of my stories have either been inspired by music or were written while there was music playing. ‘Shem-el-Nessim’ was the exception, but you’ll see that every story in The Bumper Book of Lies has a recommended soundtrack, suitable for listening to while reading it.

“In the 1980s I was fortunate enough to play bass in a couple of bands in front of audiences at the original Marquee Club on Wardour Street, the Hippodrome in Charing Cross Road and the Camden Palace. I’d played the working-man’s club circuit in the Northeast of England before that, for my sins, sometimes going on before the strippers stripped and the hot pies were served.

“Then, later, I had a job as entertainment relations manager for Gibson Guitars and met and did endorsement work with musicians I remembered from my childhood and adolescence, such as the jazz guitarists Joe Pass and Larry Coryell. Joe was a legend I remembered from his many appearances on the Michael Parkinson chat show while I was growing up. I got to spend quite a bit of time with Joe at the Frankfurt Music Fair, and at the Gibson showroom in Hamburg I was able to present him with an Epiphone Emperor guitar. He was cantankerous, temperamental and brilliant and liked a good cigar — especially a free one.”

What would you like to tell those potential readers who may not be familiar with your work about your short story collection The Bumper Book of Lies and your novel Liquidambar?

“Visit my website, then buy and read them. My writing won’t appeal to every reader, but if you’re willing to let me take you on a journey you might enjoy where we get to at the other end — especially if you enjoy reading Mervyn Peake, Russell Hoban, Martin Amis, Franz Kafka and George Orwell while listening to Frank Zappa and Robert Johnson. A cursory knowledge of US artist Edward Hopper’s paintings wouldn’t go amiss.

“There are recurring themes and influences in my work. Liquidambar was not only inspired by the works of Hopper, it takes its chapter titles from 12 of his most famous paintings. I connected characters who looked like the subjects of other paintings in order to make a surreal, Chandleresque detective story, in which a washed-up journalist, Typo Blod, becomes an unwilling and unlikely ‘shamus’ and falls in love with the subject of Hopper’s painting ‘Summertime’.

“I’m proud of many of the stories in The Bumper Book of Lies. It’s a mix of genres, from the surreal to fantasy and science fiction, and they date from 1983 to around 1995. Most have been published somewhere in the world.”

You moved from England to New Zealand . Do you now feel yourself to be part of the (or at least of a) New Zealand literary scene? If not, is that a concern to you?

“I’d lived in Hamburg, Germany for around 12 years before I emigrated here. In spite of having worked for two years as contract editor of the New Zealand Society of Authors’ bi-monthly print publication ‘The Author’, I feel utterly disconnected from the New Zealand literary scene. The sole example I can give you of any kind of networking with the Kiwi literati is that I follow Emily Perkins and Chad Taylor on Twitter and vice versa. But I’ve never belonged to or felt the need to belong to any kind of scene in any country.”

Which writers or other artists have been the major influences on you, and which writers do you especially enjoy reading now?

“Russell Hoban, Mervyn Peake, Richard Brautigan, Sam Shepard for his short fiction, Kurt Vonnegut, Franz Kafka, Billy Collins. I’ve been enjoying re-reading George Orwell lately, Keep The Aspidistra Flying, as well as the non-fiction works such as Down and Out In Paris and London, Homage to Catalonia and The Road To Wigan Pier. I also admire Martin Amis, especially London Fields, and Alain de Botton’s writing on philosophy.”

Which writing-related project are you especially proud of?

“To coincide with London-based and US-born writer Russell Hoban’s 80th birthday in 2005, I edited and contributed to the commemorative book 80!, which was published by Bloomsbury in the UK and supported by Liz Calder. The book and most of the accompanying merchandise were designed by my girlfriend Elisa, and the entire project was a joy from start to finish (apart from a scary interlude during which we lost all our page layouts in a hard drive crash and didn’t have a backup).

This project culminated in Hoban fans from around the world — brought together almost entirely by goodwill and the galvanising force of the internet — travelling to London for a weekend of Hoban-related festivities; including a coach trip to Canterbury, scene of some of the action in his novel Riddley Walker, and a very moving reading from the book in the cathedral’s crypt, by Eli Bishop, who maintains the Riddley Walker annotations website.

I encourage everyone who’s interested in discovering a life-changing body of work to read Hoban’s Kleinzeit, followed by Riddley Walker and what I consider to be his masterpiece, Pilgermann. Expect to be changed.”

What are you listening to at the moment?

“A perennial in my iTunes library is Scottish songwriter and former Doll By Doll frontman Jackie Leven, an inspiration to the writer Ian Rankin in his book Jackie Leven Said. There’s something about Scottish music, apparently: I also love The Blue Nile, and I’m currently overdosing on Justin Currie, the former Del Amitri frontman, who has just released another solo album, The Great War. What else can I tell you? Jaco-era Weather Report, John Martyn, Van Morrison, The Strawbs… I could go on, as you can tell.”

Book availablity

The Bumper Book of Lies is available from Chris Bell’s website.

Liquidambar is available from Chris Bell’s website, from Amazon UK, and from Amazon US.

Chris says: My blog posts appear here (although the site is currently down, as our director-general was too miserly to pay the hosting fee!): www.NZBC.net.nz