With a new analysis showing that rapid sea level rise is going to hit Aotearoa earlier and harder than expected – with Wellington one of the areas to be worst hit – this feels like a good, or at least appropriate, time to bring back my poem “The Last Days of the Coastal Property Boom”, first published in my 2016 collection New Sea Land and then republished on the excellent Talk Wellington blog.

We need to reduce emissions, massively and urgently, but we also need to deal as best we can with the climate effects that are already coming – worse floods, worse droughts, more sea level rise. Check out the draft National Adaptation Plan and have your say by 3 June.

The Last Days of the Coastal Property Boom

Lights on, curtains drawn, ‘Ode to Joy’

turned up loud to drown the pounding sea —

habits of prosperity surviving awareness of its end.

But uncurtained morning shows the ocean

nearer by a day, the last remaining dune

barely a memory of marram grass and halophytes.

High tide casts driftwood to the bottom step,

spume splits paint flakes from seaward-facing walls,

decking warps and peels as foundations wash away.

This was prime property when they saw it first,

the retirees’ dream of a quiet cottage, snug

between tarmac’s end and the start of the dunes.

They saw the waves and wondered, paced

the reassuring distance from high tide to front gate.

The LIM report should have warned them

but lawyers hired by those with most value to lose

had overturned the Council’s plans

and the LIM report said nothing.

The estate agent’s hectic glibness, the bank’s eagerness to lend,

lulled their fears to a vague and distant concern.

They found an insurer who would cover them,

cocooned themselves in pensions and furnishings,

paid no attention as Greenland and West Antarctica

spritzed meltwater into the rising sea.

That was the stuff of one-minute world news roundups,

helicopter shots of nameless, faceless, drowning refugees

in lands a reassuring hemisphere away.

Until the coastal defences failed, until first-world cities

were sent scrambling backwards from the beaches,

a planet-wide Dunkirk unfolding in reverse.

Now the children call them daily, desperate

for them to make the move inland. Now the house

rises and falls to the rhythm of the tide.

Now the last of their furniture vanishes,

hand-carried down the narrow strip of land

to the sympathetic darkness of the moving van.

They emerge defeated, encircled by cameras,

the human-interest story of the moment,

the last of this rich coastline’s climate refugees.

The van departs for the hinterland, where tent towns

sprawl cold across a wind-assailed plateau.

The coast reverts to sea wrack and bird call.

Waves take all but their house’s foundations, latest

and most miniature of reefs. What remains

is memory, that widest, all-consuming sea.

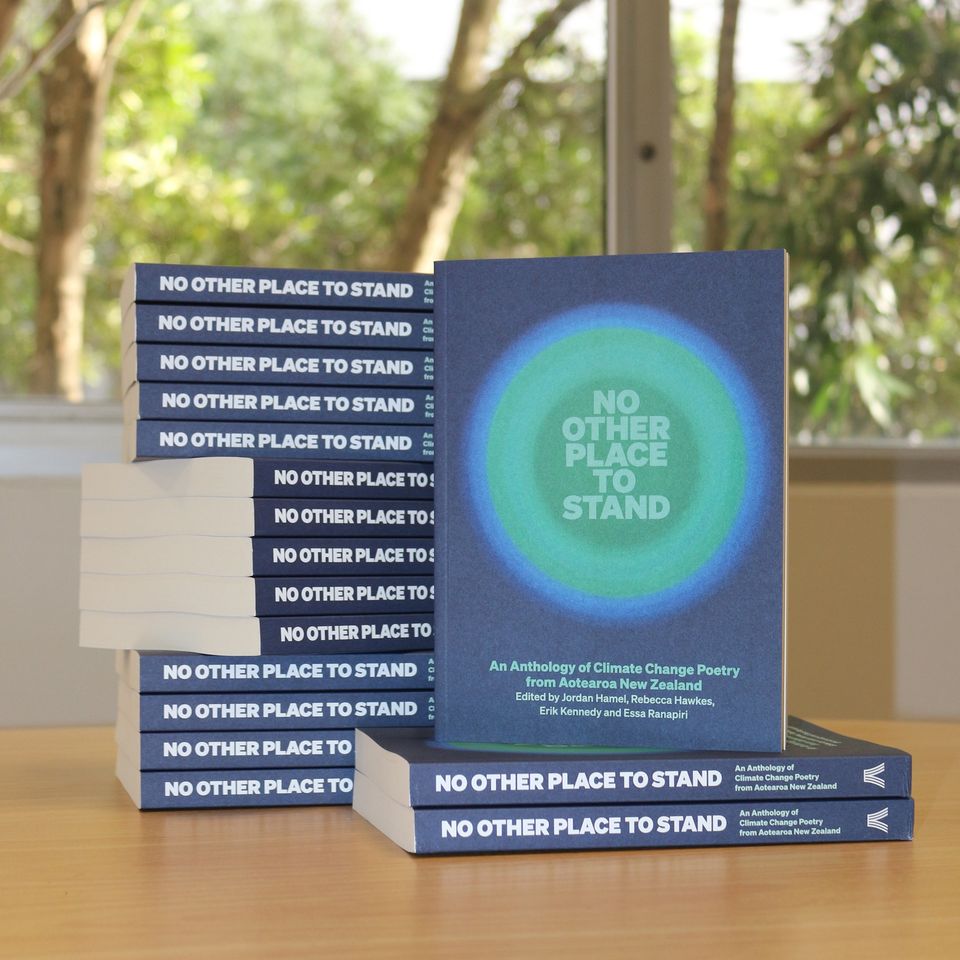

From Tim Jones’s poetry collection New Sea Land (Mākaro Press, 2016)