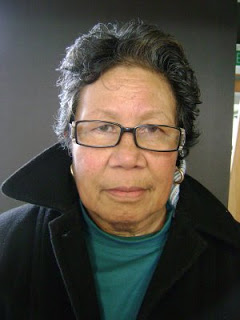

Earlier this year, I reviewed Penina he magafaoa and Takai, two collections of poetry written in English by Lee Aholima (top author photo) and translated into Niuean by his mother Nogi Aholima (bottom author photo). Since I enjoyed both books, and have an interest in literary translation, I wanted to find out more about them – so Lee and Nogi kindly agreed to be interviewed for this blog.

First of all, congratulations on the publication of both Penina he magafaoa and Takai. What can you tell me about the books? Where can interested readers find more information about them, and how can people buy copies?

Lee – Thankyou. The poetry in the books were written from the period 1993 to 2008. I started out posting the poems from Penina he magafaoa on the Niue Global Community mailing list and then someone suggested that I apply for a Creative NZ grant in 2006. I also posted a few from Takai on the mailing list. The idea of bilingual poetry books was to promote the language and to preserve our cultural heritage. Also the idea that I would have a better chance of getting the grant as I had my own doubts about the quality of my poems after submitting them to a couple of publishers. The poems were written in English first and then my mother translated them.

You can find both books in most libraries in Auckland. They are also in a few university libraries and libraries overseas. You can buy them from me via the PublishMe Shop or buy them from South Pacific Books Ltd.

Are these the first poetry collections to be published in both Niuean and English?

Lee – Tose Tuhipa the editor believes they are.

When you started work on the poems in these collections, was it always the plan that they’d be published in both languages?

Lee – Yes and no. Yes when I wrote those poems for Penina he magafaoa in 2006. They were short monologues that I was going to attempt to write in Niuean myself. I then recruited my mother to help me when I realized it wasn’t going to be easy. No too in that a lot of the poems in both books were already written back in 1994-1995.

Has there been a lot of translation from other languages into Niuean? How about from Niuean into other languages? Has fiction and poetry by John Pule been translated into Niuean?

Nogi – There’s been a few done by others through the Learning Media – but all junior reader stuff for learning of the language – both from other languages into Niuean and a few specially written Niuean readers into English and into other PI languages. I don’t think that any of JP’s work is translated into Niuean.

Lee – The biggest stockist I know of in New Zealand of Niuean books is South Pacific Books Ltd out in Bethells Beach. They would be lucky to have a dozen books and most of those are for learning the language. The most well known translation of an English book is the bible. I don’t know if there are many if any books translated from Niuean into another language. I am not sure if any of John Pule’s books have been translated into Niuean.

What specific issues and decisions were involved in making these translations?

Lee – One issue was transliteration. I didn’t mind transliteration of words not in the Niuean dictionary. I was keen to keep the names of people and places intact in English. My mother seemed happy to transliterate everything including names. My mother had some freedom with translation so there was some creativity in creating a Niuean version of some of the English sentences – e.g. my version ‘satyrious in their love’, her version ‘planting seeds at random’ or something like that.

Nogi – Transliteration is a big issue – A lot of the words used in the poems do not exist in the Niuean language and that does not include place & people’s names. The Niuean dictionary is full of transliterated words & I don’t believe that that is unique only to the Niuean language. I don’t see the point of translating English into Niuean & retain many of the English words /names, etc: or to be using too many Niuean words to describe its meaning. And it’s poetry not story writing. I find that if the topic or the environment in the poem is familiar, then it’s easier to translate. There’s never been a Niuean poet writing Niuean poetry in Niuean nor writers of any sort. The only other book besides the bible that is in Niuean & English is the book “Niue – A History of the Island” & it’s published jointly by the Institute of Pacific Studies of the Sth Pacific University & the Govt of Niue. And the writers – all bilingual Niueans like myself.

What response have you had from the Niuean community, both in New Zealand and on Niue, to the publication of these books?

Nogi – The only response I’ve had about the 2 poetry books are from my close palagi friends here in the deep south & they can only comment on their reading of the English versions. They were very positive about the books.

Lee – I am not sure if the Niuean community has completely embraced the books. Some have enjoyed them. What I have heard is that older people have some reservations. There are some who criticize things such as use of transliteration when there is already a word for it. And there are some older folk who are not used to the creative use of the language – they prefer literal.

I enjoyed the science fiction poems in Takai, such as “Liogi lanu lau kou” / “Green Prayer”. Do you read a lot of science fiction, and do you have plans to write more?

Lee – Yes I pretty much have cleaned out the Wellington Library and read all of the best sci-fi books in the library in the time I lived in Wellington. I would like to write some more but they will be few and far between. I read science fiction because more often than not it is based on bleeding edge science and technology and I like to escape. However my poems tend to be religious, philosophical, political and social commentaries as well as observations of things.

Which poets have had the most influence on your work, and which poets do you most enjoy reading? (Of course, these might be one and the same.)

Lee – I read more poetry now but nobody has really influenced me with these 2 books. I did buy Playing God by Glenn Colquhoun to have a read of it. I don’t find reading other people’s poems always that enjoyable, unlike reading a sci-fi. I do like writing poems though and reading my own – they are more a classification and posterity of my thoughts at the time hence the date at the bottom.

How do you see the future of the Niuean language?

Nogi – Niueans are not as strong as other Pacific Islands nations i.e. Samoans at holding onto their cultural heritage especially the language or dance, etc here in NZ. I don’t really understand poetry as such but I do try to understand so as to translate them. Most Niueans are here in NZ and nearly all or all NZ born Niueans can not speak or understand the Niuean Language. This apathy to the culture will eventually lead us to obscurity/obliteration culturally unless we as Niueans get involved in some way.

Lee – I am not really sure. For me I just have to try and do my bit with my mum to preserve the language.