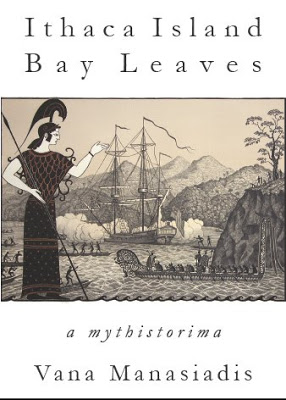

Vana Manasiadis was born in Wellington in 1973. She studied English and Classics at Victoria University, and later completed an MA in Creative Writing there. For the last few years she has been living in Crete, and travelling whenever possible, but she plans to be back on Wellington’s South Coast at the end of the year. Her poems have been published in a variety of journals, and her first collection of poetry, Ithaca Island Bay Leaves, was recently published by Seraph Press.

Vana Manasiadis was born in Wellington in 1973. She studied English and Classics at Victoria University, and later completed an MA in Creative Writing there. For the last few years she has been living in Crete, and travelling whenever possible, but she plans to be back on Wellington’s South Coast at the end of the year. Her poems have been published in a variety of journals, and her first collection of poetry, Ithaca Island Bay Leaves, was recently published by Seraph Press.

What was the genesis of Ithaca Island Bay Leaves? Did it start life as your project for the MA in Creative Writing at Victoria?

An earlier version of Ithaca Island Bay Leaves did end up as my MA folio, but my idea at first had been to explore that quite antipodean rite of passage commonly known as the OE. I was drawn to questions of mobility, transferability, and the various notions of home like comfort, familiarity, repose.

But, I didn’t get very far with my tales of the backpacker before the family stories of movement and flux blew in. My grandmother’s in particular, and then my mother’s. They both had/have quite conflicted relationship to moving and movement, to home and time; and I became interested in those tensions, and about people’s desire and ability to adapt and re-invent themselves, to settle or not settle.

So, the book became about my family’s various movements, and also about the various movements of figures from ancient history, as I’ve imagined them. (And, because I have difficulty conceiving of time as linear, everyone ended up sort of co-existing, crossing over countries and years).

I suspect many readers of this blog won’t be familiar with the form of a mythistorima – I certainly wasn’t! What is a mythistorima, and why did you choose this form for your collection?

I really like this question, because it gives me a chance to explain! Although mythistorima specifically means ‘novel’ in modern Greek, and also more generally ‘fairytale’ or ‘fantasy’, the etymological meaning (perhaps not surprisingly), is myth and history combined – from the time when people disseminated myths and (his)stories by word of mouth. I really like the fluid and undisciplined nature of speech and so I decided to kind of unfix the form of Ithaca and assume oral language with its tangents, fillers and pauses, as the governing concept. I tried to make sense of all the different forms in the book as transcripts, or fragments, then pieced them together so that they might ‘tell’ a kind of story while still remaining a little elusive.

Is there an identifiable tradition of Greek-New Zealand writing, or New Zealand writing about Greece, and if so, do you see Ithaca Island Bay Leaves as part of this tradition?

I’m not really aware of an identifiable tradition of Greek-New Zealand writing, but I could perhaps point to Michael Harlow who has Greek-Ukrainian heritage and whose poetry I’d say very strongly reflects an ‘older’ or ‘other’ world co-existing simultaneously with the here and new. In terms of New Zealand writing about Greece, there’s naturally a body of academic writing about ancient Greece via classics departments, and some non-fiction like travel writing and historical writing – for example on the battle of Crete.

In Ithaca I was interested in exploring ideas for which the country Greece became a bit of a vehicle. But, there’s no denying, I am of Greek descent, and so the whole thing becomes a bit chicken and egg.

I have to admit that I’m a little cautious about categorizations such as ‘Greek-New Zealand writing’. I think they can be useful in some situations (like this one!), but they have the potential to be limiting too. I went a bit nutty recently (then felt bad), when some new work which had nothing to do with Greece, was accepted by a publication and labeled Greek-New Zealand writing because I’d written it.

What has been the reaction to Ithaca Island Bay Leaves from readers of Greek descent in New Zealand, and in Greece and Crete?

So far my sample size is quite small, and I’ve only recently got back to Crete, so don’t have much feedback from this end. Readers of Greek descent in New Zealand seem to have related to the linguistic and cultural meeting points; and to the moments of loss, being-at-a-loss, slight absurdity. An older second-generation Greek woman said she cried, and that was really amazing for me – to hear that.

Are you involved in the poetry scene where you now live, and if so, can you tell us a little about it?

I haven’t really found a poetry scene in the town where I’m living, maybe it’s behind an amazing hidden door and I just haven’t discovered the secret handshake. I can say that I went to a talk tonight on Sappho which is part of a series of talks on various poets organized by a kind of bar/arts centre here. There’s a lot of interest or reverence or passion for poetry and literature generally here, and tonight’s question-answer time turned into a very animated affair as usual. So maybe I could say that I haven’t come across that many writers, but it seems that pretty much everyone feels very strongly about writing.

The production quality of Ithaca Island Bay Leaves is very high (as it has been for all the books published by Seraph Press). Were you heavily involved in the design of the book?

Helen Rickerby, of Seraph Press, did an amazing job with the design of Ithaca, and she was really wonderful to work with. The whole production aspect of the book was so easy and stimulating and a very positive experience.

We had similar ideas about the look of the book, about how things like the font, and the amount of space on the page and around the words could mirror the tone of the book. We liked the idea of the words and lines looking like loops of crochet, and seeming more frail than emphatic.

Also, it was Helen’s idea to have an image of my grandmother’s crochet on the inside cover, and she took the beautiful photograph of Island Bay on the back cover to complement Marian Maguire’s lithograph on the front. I’d been in totally in love with Marian Maguire’s work for a long time so excited to have Athena Observes a Fracas for the cover.

Have you been satisfied with the critical reaction to Ithaca Island Bay Leaves, in terms of both the number of reviews and the reactions of those who have reviewed it?

To date the book has been reviewed in the New Zealand Herald and the Otago Daily Times. The Herald review, by Paula Green, was a really positive and generous review, and (of course) I felt that she really got the book when she said, ‘It is a way of telling stories, and a way of being told’.

The ODT review, by Bluff resident Hamesh Wyatt, said something along the lines of fascinating, funny and a bit random. Lynn Freeman on “Arts on Sunday” – and I don’t know if this counts as a review – said nice things during her interview with me on Radio New Zealand too, and that was really exciting for me. I’m pretty happy and surprised to have had any critical response at all – but Helen has done some great work publicising in an environment where poetry, especially from small presses, sadly doesn’t get a heap of attention.

Which poets have had the most influence on your writing, or are among your personal favourites? Are there any whom you’d especially recommend?

Having recently seen Jane Campion’s Bright Star, I feel I have to say that John Keats was one of the first poets that really mattered to me. I remember receiving his embrace of life and earthy decay as epiphany.

In more recent times, I’ve really enjoyed and been inspired by Greek poet Nasos Vaghenas, Derek Walcott and Anne Carson – particularly Anne Carson – for her play with forms, and the unpredictable, magical, moving, powerful combinations of those forms, and times, settings, and voices. And, she knows a lot of stuff. When I read Anne Carson I feel in the presence of both raw heart and razor-sharp mind. I’ve also been reading a bit of New York poet Kenneth Koch, and his vitality, energy and again dancing and surprising combinations of images and directions have been pretty elating.

But, I have to admit that I read more prose than poetry, and at the moment Roberto Bolano has my favour. Entirely awed by his epic 2666, I’m now reading his Savage Detectives which has me equally amazed and moved and feeling very alive. His prose is active and declarative, and again, very intelligent. His characters are both egotistical and vulnerable at the same time, are vexed by longing and hunger.

Do you have a plan for how your writing career will unfold? If so, and if it isn’t a secret, where do you see yourself and your writing in five years’ time?

I should pay you for asking me this. I don’t have a plan, I feel like I should, but I don’t. It’s been five years since I wrote the first version of Ithaca, and although I’ve been working on other projects since then, its been in a very uncommitted, very inconsistent way.

My most stubborn project has grown out of a conversation with my sister who directs and writes for theatre. She had been working on a script and was interested in including prose written by one of the characters, and suggested I contribute the writing. The experience of collaboration was energizing and has made me think that I’d like to work more collaboratively in the future in general.

Writing is so solitary but it doesn’t have to be, and working on Ithaca has made me think about community. Sure, there’s often a writerly community, and the potential for numerous discussions, influences, inspirations, but ultimately a work ends up with a single author’s name on it, and I’m becoming quite interested in ideas of likeness and kinship. Let’s say that in five years I’ll be part of some collective writing type thing, and merging lots more.

Sample Poem: King of Mycenae

Menelaus was known as a bit of an eccentric.

Over a pint at The Arms, he’d boast about this

and that: his kidnapped wives, his wagered wars,

his days as a people smuggler. He’d sailed on

the Queen Mary, ridden on the Orient Express,

eaten quince. He was the talk of Greymouth.

For a longer poem from the collection, see Tuesday Poem: Ithaca.

Book Availability

Ithaca Island Bay Leaves is available from the publisher, Seraph Press, and from independent bookshops around New Zealand, including Unity Books; Otago University Bookshop; The Women’s Bookshop (Auckland); Parsons Books (Auckland); Scorpio Books (Christchurch); Time Out Bookstore (Auckland); and Page & Blackmore (Nelson).

It can be ordered through any bookshop, using its ISBN: 978-0-473-15235-2

Finally, if you have a jones for author interviews, you can view all the author interviews on my blog by using this search.